Post: 26/06/2016

On Tuesday the Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (Defra) will announce the results of OpenDefra, its ambitious project to make at least 8,000 datasets freely available to the public over the course of a year.

OpenDefra was launched in late June 2015 by Environment Secretary Liz Truss. Yesterday was the deadline for Defra network organisations to meet their targets for publication of open datasets, as recorded on Data.gov.uk (DGU).

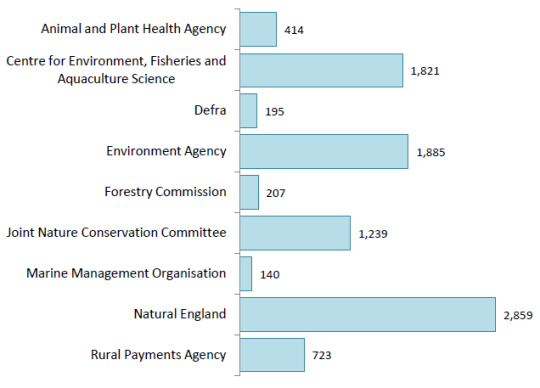

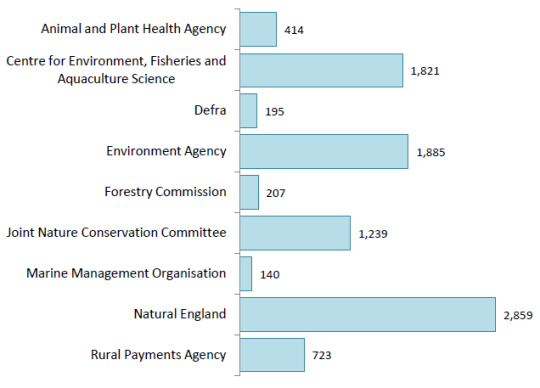

According to DGU, Defra has comfortably exceeded the 8,000 dataset target. The following nine Defra organisations have published a total of 9,573 datasets over the past year, of which 9,483 are re-usable as open data.

Download: full list of datasets

Defra’s own final tally may be slightly different. Defra has been cagey about exactly which organisations within its network were expected to contribute to OpenDefra or the precise targets they were given.

I’ve assumed that most smaller bodies, such as National Park authorities, were out of scope. However its disappointing not to see anything from the Drinking Water Inspectorate, the Veterinary Medicines Directorate, and (in particular) Kew.

What is a dataset, anyway?

9,483 datasets is clearly a lot of open data. But one of the minor controversies around OpenDefra is what exactly counts as a “dataset” for purposes of recording on DGU.

There are legitimate reasons why it might make sense to document a large body of data as a collection of datasets instead of as a single dataset. On DGU this is left to the discretion of individual publishers, so there is a wide range of practice.

By some small miracle Environment Agency has published 1,885 open datasets on DGU in the past year, out of a total 1,535 datasets (including unpublished and non-open) on its own National Dataset List.

I don’t think this is a deliberate attempt to “game” the OpenDefra target. Many EA datasets are technical and complex, and need more explication on DGU than they do on the simpler National Dataset List.

However it’s a matter of judgement whether the water body data released to support Water Framework Directive river basin management plans should have been catalogued on DGU down to the level of individual catchments (550+ datasets), or whether the Water Quality Archive needed a DGU record for each area and year (800+ datasets).

More significant is Natural England’s decision to create a DGU record for each of its post 1988 agricultural land classification (ALC) surveys (maps and reports scanned from paper to PDF). This is certainly a large project, but NE’s own blog post describes the ALC surveys as a “dataset” (singular).

By “salami-slicing” the ALC dataset on DGU into 2,699 datasets, rather than one, Natural England has made itself the most prolific Defra publisher of open data. Without this decision it’s unlikely the Defra network as a whole would have met the ministerial OpenDefra target of 8,000 datasets in a year.

Beyond the OpenDefra 8000

Of course that target of 8,000 datasets was always a bit arbitrary. Whether the “real” number of open datasets released by Defra is higher or lower than that, the target has been an effective mechanism to drive the release of many thousands of open datasets over the past year.

The more interesting question is: what will OpenDefra do next? I suggest several challenges:

Realistically the vast majority of open data released by the Defra network will be of only niche or historical interest. However some datasets will have significant potential for re-use. Certain categories of data have obvious value: flood risk, LiDAR, air quality, water quality, etc. But is there more Defra publishers can do to help the data community sort the wheat from the chaff? (Given, as always, the limitations of the DGU platform.)

Defra should clarify its strategy for future development and publication of data assets. It is generally unclear which open datasets are one-off releases and which have been published with the intention of future updates. This makes considerable difference to the re-use potential of the data.

Defra organisations still have substantial reserves of unreleased data. Given the volume of data released over the past year it would be uncharitable to suggest Defra publishers have only picked the low-hanging fruit. However there has evidently been no real breakthroughs in the underlying barriers that prevent release of some core datasets, such as the Rural Land Register and EA’s National Receptor Dataset. It would help to hear from Defra on the “lessons learned” over the past year, and what the open data community can do to help inform arguments for unlocking further public data.