Post: 28 June 2015

This week the UK Environment Secretary, Elizabeth Truss, gave a speech in which she announced that:

Over the next year we will be making 8,000 datasets publicly available, in the biggest data giveaway that Britain has ever seen.

Tech City people, developers, entrepreneurs, scientists, investors, NGOs, anyone with a great idea, will have full and open access.

Alex Coley, who is Defra’s lead on open data and transparency, posted this:

We have set up an accelerator project within Defra, with key people from across our organisations to build on some of the great work already started in parts of Defra. We will be working with external experts and our data users as we work out the best way to meet the challenge that our Secretary of State has set.

Truss also gave an interview on BBC Radio 4 (from 33:15), in which she expanded on the case for open release of Defra data, mentioning in particular potential applications in precision farming, monitoring the marine environment and citizen science.

But what datasets does Defra have, and what exactly is the department planning to release?

The Defra Network

Defra (the Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs) holds a substantial amount of data in its own right. However the department also has oversight of a network of executive agencies and non-departmental public bodies. See Annex II in Defra’s Open Data Strategy for a full list.

It’s unclear exactly which organisations will be involved in the Open Defra initiative, but parts of the Defra Network are more “data-rich” than others. In particular: the Environment Agency, Natural England, the

Rural Payments Agency, the Marine Management Organisation (MMO), the Centre for Environment, Fisheries & Aquaculture Science (Cefas), the Food and Environment Research Agency (Fera), the Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC), and the Animal and Plant Health Agency (APHA).

Defra dataset lists

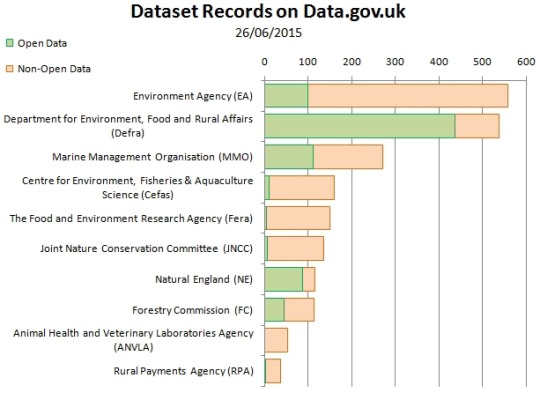

I have extracted an inventory of 2,328 datasets held by Defra organisations from Data.gov.uk. About 37% of these datasets are already available for re-use as open data.

That list is based on the Defra publisher hierarchy on DGU, which (in addition to the network members mentioned above) includes two non-ministerial departments – Ofwat and the Forestry Commission – and a range of other bodies such as national park authorities and advisory committees. It also includes the Canal & River Trust, which is now a charity. (Note that most of the APHA datasets are still listed under the agency’s old name, the Animal Health and Veterinary Laboratories Agency.)

According to the DGU inventory these are the organisations that hold most of the Defra Network’s data:

The DGU inventory is useful for insights into the types of data held by each member of the Defra Network, but it is highly unlikely to be complete or reliable. As Truss says, much of Defra’s data is “hidden away” …

Environment Agency open data

Independently of the new Open Defra plan to release 8,000 datasets within a year, Environment Agency has been developing its own ambitious open data programme. Two significant releases of flood data in February and December last year were followed by news earlier this month that EA would release all of its LiDAR datasets as open data from September 2015.

Until relatively recently Environment Agency had a policy of charging for commercial re-use of their most economically valuable datasets. EA has now said any new products will be packaged for open data release instead, and has tentatively announced a plan for all existing charged data products to become open data, in three tranches with target dates of April 2016, April 2017 and April 2018.

You can read more about the progress of EA’s open data programme in the papers of the Environment Agency Data Advisory Group. (I am a member of EADAG.)

It seems likely this week’s Open Defra announcement will put some skates under the Environment Agency plan or at least create pressure to front-load its schedule for conversion of charged data to open data.

Environment Agency has also developed a list of the top 79 priority datasets it is assessing for release as open data over the next six months. In addition to the LiDAR data this list includes (as highlights): Authorised Landfill Sites, WEEE Producers Public Register, Potential Sites of Hydropower Opportuniy, much more flood data (the Flood Map for Planning, the Updated Flood Map for Surface Water, Modelled Flood Outlines and Recorded Flood Outlines), and numerous Water Framework Directive datasets.

Behind this is a deeper reservoir of data assets, many of which have not previously been considered as potential products for public re-use. EA has released an early version of a National Dataset List that includes 1,385 entries.

Data assets of other Defra Network members

So far the national media have paid little attention to the Open Defra announcement, but Truss’s speech was picked up by trade press in sectors that follow Defra policy closely: Farmers Weekly, Horticulture Week and Pig World.

If nothing else, a big push from Defra could go a long way towards reducing the urban (and particularly London-centric) focus of interest in UK open data. I think that would be a healthy development.

However, while I’m familiar with Environment Agency and Natural England datasets, I only superficially understand uses of data within other Defra organisations such as the MMO, Cefas, Fera, etc. That makes it difficult for me to judge which of their datasets are significant and which have only niche potential for re-use.

I made a bit of headway on this in 2013-14 when I was on the Defra Transparency Panel, and identified a few datasets that I thought would make useful open data releases, such as Fera’s FC24 food contaminants database, VMD’s Product Information Database, the National Forest Inventory, and the Rural Land Registry. However there are likely to be many examples of equal or greater interest that I am overlooking due to lack of specialised knowledge.

On the other hand the scale of Defra’s plan may make it unnecessary to identify and prioritise datasets for release based on their individual value. Releasing a sufficient volume of niche datasets can be just as powerful as releasing a few obviously important datasets, due to multiplier effects from linking the data and incremental accumulations of value along supply chains.

Defra has already highlighted the considerable amount of earth observation data coming on stream from the EU’s Copernicus programme. (Defra is the conduit for UK involvement in Copernicus.)

Truss also mentioned air pollution data as an area with potential. Defra already has an information resource dedicated to air pollution data but I understand there is considerably more detail that could be released, including historical observations.

I also understand Defra are preparing a (rather overdue) release of noise data for England.

Is 8,000 datasets in a year achievable?

What I like most about the Open Defra initiative, at this early stage, is that it has a simple focus: open data release, to a deadline that doesn’t leave much room for consulting stakeholders, building data portals, developing APIs, or other displacement activity.

It’s difficult to tell how much enthusiasm there is for open data within Defra and its agencies. Most of my contact is with open data practitioners, so I’m mindful of confirmation bias. Buy-in from ministers is a positive sign, but ideally there should be a cultural shift as well. But at least I no longer have the sense that Defra is only engaging reluctantly with the open data agenda at the prodding of the Cabinet Office.

I am not entirely confident the Defra Network actually has 8,000 datasets that can be safely released as open data. However that may be a matter of definition. As PASC observed in a report on open data last year:

Some data sets are small and others large. And it is possible for departments to get more data out by publishing it in smaller bundles or updating it more frequently, in such a way that there is little or no extra public benefit.

8,000 is a large enough number to motivate Defra organisations to push out as much open data as they can, but it is just a number. The important thing, in my view, is that Defra should release a substantial proportion of its considerable data assets for open re-use.

Copernicus observation data and the EA open data programme will go a long way towards the target, but I hope we will also gain a better understanding of the resources available from other Defra organisations.

Some, such as Natural England and MMO, are already aligned to support open data policy. The status of data held by other organisations will need clarification – Fera for example was part-privatised earlier this year, and Kew has recently set up a consultancy spin-off to “sell commercially useful information”.

Photo credit: Defra by Owen Blacker (CC BY-NC 2.0)