Post: 24 January 2012

Yesterday the British Dam Society held an evening meeting on Reservoir Risk Classification. The BDS is a member organisation mainly for engineers who inspect or work on dams and reservoirs, but to their great credit they stream their meetings online and provide open access to non-members.

The meeting was based around two lectures with a Q&A at the end. Tim Hill from Mott MacDonald spoke first on the Reservoir Inundation Mapping Project completed on behalf of the Environment Agency in December 2009. Tony Deakin from the Environment Agency then explained the consultation on proposed options for reservoir classification that the EA is currently running.

The main point of the meeting was to explain the EA’s new approach to assessment of large raised reservoirs in England and Wales. Provisions of the Flood and Water Management Act 2010 due to be implemented in October will introduce a new “risk-based” safety regime for reservoirs that hold more than 25,000m³ of water above ground level.

“Risk-based” essentially means that inspection and supervision requirements will apply to reservoirs identified as “high risk” and not to the remainder, so identifying and setting the criteria for that group of reservoirs is quite important for engineers and reservoir operators (or “undertakers” as they are called).

My own interest is more generally in flood risk as a geographic peril and the availability of information for insurance underwriting and exposure management purposes. For me this meeting was an opportunity to find out whether there was likely to be any additional release of useful public information on the risk of inundation from reservoirs.

(Spoiler alert: No.)

Reservoirs in the UK have a very good safety record and there have been no incidents resulting in loss of life since legislation was introduced in 1930. The risk of a dam breach or uncontrolled release of water from a large reservoir is generally considered remote, but if it actually happened the loss of life and damage to property could be catastrophic. Reservoir inundation is a “low likelihood, high severity” event.

In June 2007 cracks appeared in the Ulley Reservoir near Rotherham in South Yorkshire during a burst of torrential rain. Three villages were evacuated and the M1 motorway closed while emergency work was carried out to reduce the water level and repair the damage. This was of course only one incident in a summer of serious flooding.

One of the requirements of the Pitt Review into the 2007 floods was that:

The Government should provide Local Resilience Forums with the inundation maps for both large and small reservoirs to enable them to assess risks and plan for contingency, warning and evacuation and the outline maps be made available to the public online as part of wider flood risk information.

The Reservoir Inundation Mapping Project produced an inundation outline map, based on a “worst-case scenario” breach, for each of the roughly 2,100 large raised reservoirs in England and Wales that hold more than 25,000m³ in water. Those outline maps were provided to the undertakers of the reservoirs, and in December 2010 were also put on the Environment Agency’s public website.

The inundation outlines and geographic locations of the 2,100 or so reservoirs (excluding those operated by the MOD) are also available from the Environment Agency as data sets for commercial re-use. (These are among the EA data sets that I have recently argued should be released as open data.)

This means the Government has met the letter of the formal recommendation in the Pitt Review. However the Pitt Review contained a whole chapter on effective management of dams and reservoirs. It recognised security concerns but made it clear that the public needed to be aware of the risks: “Secrecy leaves us in the curious position that there is a strong chance that we now defeat our own ends.” Pitt cited as “best practice” an example of flood alert mapping from a system of dams in Switzerland.

The outline maps by themselves are little more than a talking point, sufficient to raise public awareness that reservoirs exist as a potential source of flooding but of no real use for preparedness.

Large raised reservoirs are placed in one of four categories (A, B, C or D) and for those in Category A or B more detailed maps have been prepared. These maps show the extent, depth, velocity, hazard, time of arrival and time of peak of potential inundation following a breach.

These detailed maps are Restricted, which means they are not made public but are in principle issued to Local Resilience Forums for emergency planning purposes. Reservoir undertakers may view the maps by special arrangement at Environment Agency offices.

Additional information, such as critical infrastructure, is added to the Restricted maps separately and normally available only to Gold Command, the strategy group (usually police-led) that coordinates multi-agency response to an emergency.

I say the Restricted maps are “in principle” issued to Local Resilience Forums, because there are reasons to question whether everyone who needs to have access really does in an emergency situation. An internal Environment Agency report on lessons learned from last year’s Exercise Watermark emergency exercise included the following on access to detailed reservoir inundation maps:

There were difficulties in accessing security restricted off-site detailed reservoir inundation maps during the core exercise. These are currently stored securely on the National Resilience Extranet (NRE) hosted by the Cabinet Office. As an organisation, we use the NRE as a planning tool, and have arranged for named individuals to have licences and particular computers to have additional software installed. This makes it challenging to access the NRE during incidents, for example when those individuals are not present, and although we would be able to create further licences for incident rooms, feedback indicates that this system is not the right solution for our organisation to access those maps.

Based on the response to a question I asked at yesterday’s BDS meeting, even the Category of individual reservoirs will not be made public in future. This means members of the public may have no real idea whether a reservoir local to them is one of the relatively small number that presents a serious risk to life in the event of a breach.

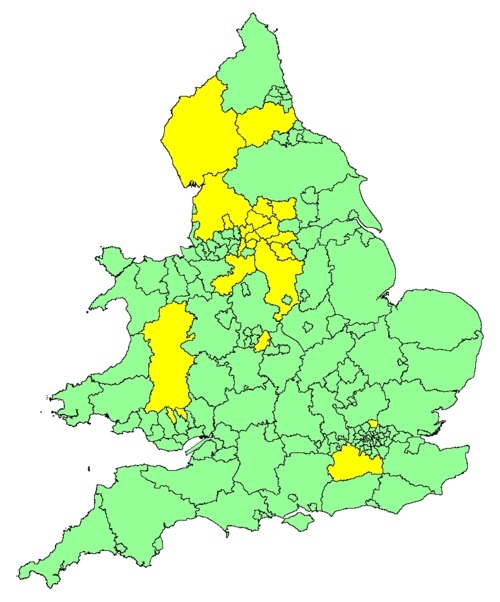

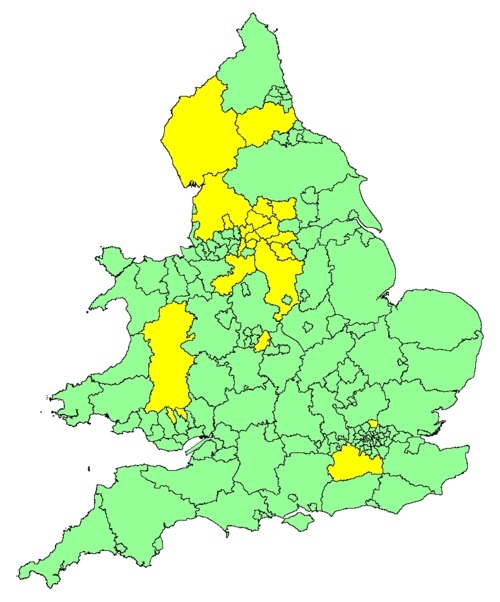

In late 2010 DeFRA funded the preparation of off-site emergency plans for about 100 “higher priority” reservoirs in England and Wales. In response to an information request DeFRA and the Welsh Assembly refused to provide a list of those reservoirs, on advice from the National Security Liaison Group. The most I was able to get was the list of local authorities given funding to prepare the off-site plans (indicated in yellow on the map below):

Although the criteria for “high risk” reservoirs under the new FWMA safety regime has not yet been finalised it is likely that this list of unidentified reservoirs will remain the focus of the EA’s risk-based monitoring.

In my view the UK’s approach on public information about reservoir inundation risk, and the resilience of critical infrastructure in general, is still overly influenced by national security concerns. It is difficult to see how emergency planners can fully prepare their communities, for example by identifying evacuation routes and procedures, if they cannot publish the more detailed inundation maps that show different breach scenarios, volumes and rates of flow, and estimates of potential loss of life and damage to property.

Local planning authorities are also under a statutory obligation to produce Strategic Flood Risk Assessments every five years and submit them for public consultation. In the past SFRAs have included information on reservoirs. It remains unclear how local authorities will continue to consult their communities fully if they cannot disclose the particulars of any “high risk” reservoirs within their area of responsibility.